Safeguarding Critical Workflows With The Dead Letter Queue Process

You have likely experienced that specific sinking feeling: an essential automation—perhaps for employee onboarding or invoice processing—runs silently in the background, until it doesn’t.

An API token expires, a rate limit is hit, or a database locks up. The workflow fails. If you are lucky, you get a generic email notification. If you are unlucky, the data that was being processed simply evaporates into the void of "failed execution logs," forcing you to manually dig through history, copy-paste JSON payloads, and restart the process by hand.

For an Internal Ops Manager responsible for organizational efficiency, this fragility is a nightmare. It creates trust issues with the teams you are trying to help. If the HR director loses one new hire's contract details because of an automation glitch, they won't care about your 99.9% uptime. They will remember the one that got away.

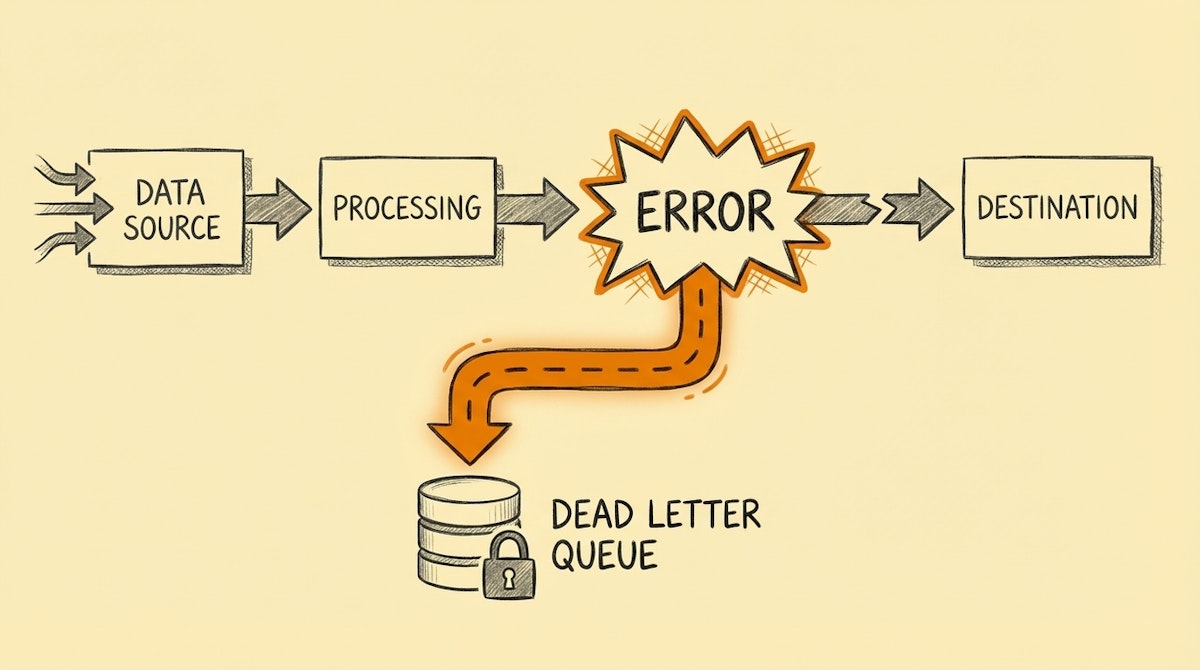

I have observed that many "no-code" setups treat error handling as an afterthought. However, we can borrow a time-tested concept from enterprise software engineering to solve this: the Dead Letter Queue (DLQ).

This isn't just about knowing that something failed; it is about capturing what failed so you can replay it later without data loss.

The Silent Failure Trap

Most automation platforms (like Make, n8n, or Zapier) have built-in error notifications. They tell you, "Scenario X failed." While useful, these alerts are often insufficient for critical operations. They alert you to the event of a failure but do not inherently preserve the state of the data at the moment of failure.

When a workflow stops halfway through, the data payload (the actual business value) is often trapped inside the platform's temporary logs. Retrieving it requires technical intervention, often under pressure.

The Dead Letter Queue Process

In systems architecture—famously used by services like Amazon SQS—a Dead Letter Queue is a holding tank for messages that couldn't be processed successfully. Instead of discarding the message or crashing the system, the architecture moves the problematic data to a side channel for inspection.

In the context of internal operations, we can replicate this process simply. Instead of letting a workflow error out and die, we route the failure to a dedicated "hospital" database (like an Airtable base or a Google Sheet).

Step 1: The "Hospital" Database

First, create a simple table to act as your DLQ. It needs to store enough context for you to diagnose and fix the issue. I suggest the following columns:

- Timestamp: When did it fail?

- Source Workflow: Which automation triggered this?

- Error Message: The raw error returned by the platform.

- Payload (JSON): The entire input bundle that failed to process.

- Status: A status field (e.g., "New", "Investigating", "Resolved").

Step 2: The Error Handler Route

In your automation tool, you need to configure an error handling route.

- In Make: Right-click a module and select "Add error handler." Connect this to a module that creates a record in your DLQ table.

- In n8n: Use the "Error Trigger" workflow or connecting the "Error" output of a node.

Instead of the automation stopping abruptly, the logic flows to this backup route. It takes the data intended for the destination (e.g., the payload meant for the CRM) and writes it into the Payload column of your DLQ table.

Step 3: The Recovery Action

Once the data is safe in your DLQ, you can trigger a notification (via Slack or Teams) that says: "Workflow X failed, but the data has been saved to the DLQ. Check it here: [Link]."

This changes the dynamic completely. You aren't scrambling to find lost data; you are calmly notified that a task has been paused and filed for review.

Comparing Standard Alerts vs. The DLQ Process

The shift here is from reactive panic to managed remediation. Here is how the two approaches stack up across key metrics:

| Metric | Standard Error Alerting | Dead Letter Queue Process |

|---|---|---|

| Data Preservation | Volatile (Logs only) | Persistent (Database) |

| Recovery Time | High (Manual extraction) | Low (Re-drive capability) |

| Team Trust | Fragile | Resilient |

Why This Matters for Operations

The goal of the Internal Ops Manager is to remove friction. However, automation itself can become a source of friction if it is perceived as unreliable.

By implementing the Dead Letter Queue process, you are essentially telling your stakeholders: "Even if the internet breaks, we won't lose your request." It acts as an insurance policy for your workflows.

Furthermore, this database of failures becomes an audit log in itself. You can review it monthly to spot patterns. Is the legacy ERP always timing out on Tuesdays? Is the new ATS rejecting specific character sets? The DLQ gives you the data to identify and fix root causes, rather than just reacting to symptoms.

Conclusion

Reliability is the currency of automation. It is easy to build a "happy path" where everything works perfectly. But the true value of an automated system is tested when things go wrong.

The Dead Letter Queue process allows you to fail gracefully. It ensures that no matter what technical hiccup occurs, the business intent—the new hire, the invoice, the leave request—is preserved, safe, and ready to be processed once the dust settles.

References

- Amazon Web Services (AWS) - Dead-letter queues: https://docs.aws.amazon.com/AWSSimpleQueueService/latest/SQSDeveloperGuide/sqs-dead-letter-queues.html